By Warren Nunn (first published Nov 2024. Updated Apr 2025)

To say that Albert Card was an eccentric individual is an understatement.

Albert Card. Photo by The Hart Co, 492 Hay St, Perth, Western Australia. Taken around 1900.

The course of his life and the events along the way are a study in the vagaries both of his character and the situations in which he involved himself.

He was the sixth of eight children born to George Card and Elizabeth Blanchard at Tunbridge Wells, Kent, England.

When the 1851 UK census was taken several months before he was born, Albert’s father was self employed as a “fly master”. This suggests he had at least two light carriages for hire; basically an earlier version of a taxi.

By 1861 George Card had moved his family about 30 miles to Croydon, Surrey, where he was employed as a plumber’s labourer. Only Albert, his older brother Frederick and youngest brother Alfred were still living with their parents.

By 1871, George was working as a stableman while Albert, now 19, was a paper hanger and painter. Younger brother Alfred was a plumber’s labourer.

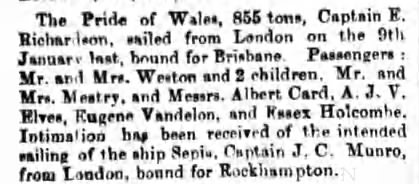

Perhaps because of his father’s death in 1872, Albert Card decided on a new life and change of scenery, so he sailed off to Brisbane, Queensland, Australia in 1875.

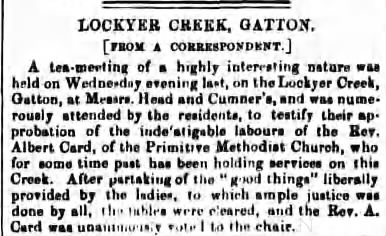

Albert Card preaches at Gatton in September 1876.

Preaching role

He appears to have been a zealous and pious young man and is mentioned in a newspaper column at Gatton west of Brisbane in September 1876 as a Primitive Methodist preacher. If Albert Card had any theological training, that is not clear, but he was referred to as Reverend Card.

Some months later, in 1877, the Queensland Primitive Methodists appointed Albert Card a minister in Brisbane.

It’s not clear what that meant but his association with the Primitive Methodists may have ended because of the tone of a letter to the editor of the Rockhampton Morning Bulletin he wrote in 1881.

In the letter, Card said he arrived in Rockhampton in 1878 as a student preacher with the Presbyterian church.

But the less-than-gracious tone of the letter suggests he had a problem with the Methodists. It reads:

Sir,—A correspondent writing in the columns of your contemporary of this morning would have done very well had he signed his name to his effusion of fulsome flattery of the Primitive Methodist ministers for the disinterestedness and zeal they have displayed in behalf of the Stanwell Church. At the present none can read that letter without the thought coming uppermost that the writer is either one of the three Primitive Methodist ministers, or a strong supporter of that Church. “Subscriber” speaks as though he were an oracle of the past supply of Stanwell; but unfortunately he is inaccurate in his statements. Had he not alluded to “the occasional visit of a student” I should not have felt called upon to scrape his buttered effusion. Three years ago I came to this town as a student (one of the students “Subscriber” alludes to) in conjunction with Mr. W. E. Hillier, and under the supervision of the Rev. A. Hay, to conduct services in connection with the Presbyterian Church in the outlying districts, and I know of my own knowledge that from August, 1878, to May, 1879, services were held by the students (Mr. Hillier and myself) once every month at least, and that during that period the indefatigably earnest and disinterested Primitive Methodist ministers did nothing to minister to the spiritual wants of Stanwell. During the time of which I speak the Rev. A. Hay used occasionally to go out on Sunday afternoon to hold service there and back into town for the evening. Mr. Sterling, another Presbyterian student, frequently visited the much neglected district, and yet “Subscriber” would have us to believe that the other churches of this town are only coming to the front now the Primitives have built a church, and waxes quite eloquent on the subject; but in his denunciations of other churches he is but squirting muddy water against a wall and will get well bespattered for his pains.

Yours. &c. ALBERT CARD.

Rockhampton, September 6, 1881.

The letter reveals that Albert Card was articulate and passionate about his convictions. But he did lack grace.

Stanwell is a rural area about 15 miles from Rockhampton. It is now best known as the site for one of the State’s largest power stations.

Speaking up

He must have been a confident young man as he was called up to speak publicly at a display of images entitled “The celebrated cities and scenes of Europe and Asia”. A report in July 1881 records that Mr Albert Card of Rockhampton had been lecturing in Bundaberg on “Bible Literature”.

Albert Card arrives in Brisbane aboard the Pride of Wales.

He is later found in newspaper records as a law clerk giving evidence in a court case in Rockhampton.

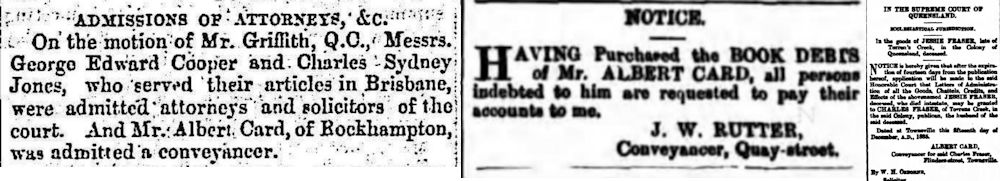

And by 1882 he is appointed as a conveyancer and sets up his own practice in Rockhampton.

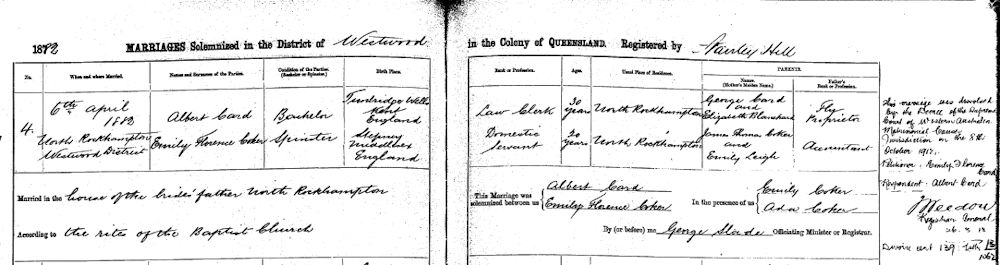

Around this time he was courting Emily Florence Coker, daughter of my great-great grandfather James Thomas Coker. Known as Florence, she and Albert married at the Coker home in North Rockhampton in April 1882.

In January 1881, Florence had given birth to a son she named Francis but the child only lived for a month. Most likely her mother delivered the infant, given she was a midwife. There’s no father’s name given on the birth certificate.

Whatever Florence’s circumstances thereafter, she had married a young man with prospects. But life with Albert Card turned out to be anything but prosperous and stable.

Albert Card and Florence Coker marriage certificate. There is a side note that details their divorce in Western Australia in 1912.

Conveyancer

Albert set up as a conveyancer and advertised his business in the Rockhampton Morning Bulletin newspaper.

Newspaper reports show Albert had diverse interests including as a member of the Central Queensland Farmers’ and Selectors’ Association and he also invested in the Rockhampton Tramway Company. But he didn’t get to see trams on the streets of the city as that did not happen until 1909, long after he left Queensland.

Albert also aspired (without success) to become an alderman of the North Rockhampton Borough Council for which his father-in-law James Thomas Coker was the town clerk. An account is told elsewhere of how James Coker disgraced himself in the role and ended in jail.

Albert struggled to make a living as a conveyancer and by 1885 he sold his debts and gave up his business. He relocated to Townsville and tried again to make his way as a conveyancer.

This is where Albert’s life starts to get really messy because of those with whom he was associated.

Why?

Because the person who bought up his debts and took on his business was John Wallis Rutter, North Rockhampton Borough Council Mayor who, like James Coker after him, was jailed for his illegal actions while a trusted public servant.

Albert Card in newspaper notices. Read on for a fuller explanation.

In a letter Albert wrote from Townsville in October 1885 to the North Rockhampton Borough Council, he said that Rutter should be disqualified from office because he was also a contractor to the council through supplying materials.

Rutter dispute

There was obviously bad blood between Card and Rutter. However, Rutter convinced council to ignore Card’s allegations and return the “spiteful” letter. In light of what later transpired, perhaps elected representatives should have paid more attention to Card’s assessments of Rutter’s actions.

Albert’s time in Townsville must have been brief because by September 1886 he and Florence are in Sydney, New South Wales. Albert was exercising his oratory skills in the Domain on Sundays speaking about temperance.

Albert also advocated for a single tax rate, unsuccessfully sought election in the State Parliament, and struggled to survive based on an 1891 court order that he pay his overdraft after having been declared bankrupt.

Then, in March 1892, Albert and Florence welcomed their only child, Harold George Blanchard Card. George was his grandfather’s first name, and Blanchard, his grandmother’s maiden name.

Questionable medical institute

By 1895 the Card family was in Newcastle where Albert became involved in the Newcastle Medical Institute, seemingly as a legal adviser. But the so-called institute seems to have been a front for taking money under false pretences.

One of the clients, Walter Grey Nicholson, sued the operator, Charles Hart, to recover fees. Hart was paid almost £20 to instruct a young man, but no training took place over the five months he was there; and then the institution went out of business.

Albert Card had written out an indenture for the young man, Henry Walter Nicholson, and denied all responsibility when challenged on the matter.

Around this time Albert Card had an association with a phrenologist, Alfred Allard, who faced court for pawning a silver watch belonging to someone else.

Spiritualism interest

Albert embraced the emerging fascination with “spiritualism” and within months was hosting events. One gathering advertised in the Newcastle Morning Herald and Miners’ Advocate, on Saturday, 22 February 1896, reads:

Spiritualism. A trance address will be delivered at the Wickham School of Arts on Sunday evening, the 23rd inst., by Mrs Hodgson. Subject: “The Nature of Spiritual Life.” Albert Card, Esq, in the chair. Collection.

Albert realised there was money to be made for such services and he was attracted to the idea of such an enterprise.

Off to Western Australia

Nothing more is known of Albert Card until around 1900 when he is found on the other side of Australia, in Perth, supposedly as a private detective. Later he was town clerk in North Perth.

A newspaper columnist wrote with a pen dripping with sarcasm in describing Albert’s aspirations to be a federal politician.

Diminutive Albert Card, whose flimsy platform is built upon Vosper’s planks, has been holding forth anent* The Sunday Times because it pointed out that Card was working on another man’s ideas.

The little man is wrathful, and this journal may yet feel disposed to give him some notice. Federal House of Representatives would, no doubt, welcome and be graced by the contribution of a private detective from Western Australia.

*regarding, or concerning.

Vilified in print

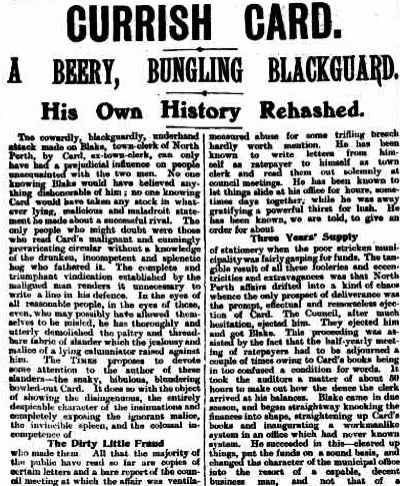

How The Sunday Times challenged Albert Card.

By January 1904, Albert became a laughing stock when The Sunday Times printed a scathing article that labelled him as “a beery, bungling blackguard”.

The article is vicious and full of legally actionable statements against Albert Card. The paper was defending the honour of Thomas Hayes Blake who’d been appointed town clerk in place of Card.

Some of the insults hurled at Albert Card were: “drunken, incompetent and splenetic hog”; “snaky, bibulous, blundering bowled-out Card”: “a noisy, meddlesome and pestiferous nuisance”; and a “small, mouthing, self-trumpeting impostor”.

Of Card’s time in the position he lost to Blake, it was so described:

“The man is reputed to know less than a 13-year-old office boy about books. He knows a good deal less than a 13-year-old office boy about figures. The capacity to run and co-ordinate and square the finances of a struggling municipality wasn’t born in him. The inclination to drink and squabble with councillors and make a fool and a hog and an idiot of himself and put things into a hopeless mess was.”

The Sunday Times also concluded that Card’s allegations against Blake were ludicrous and actionable. The paper responded with an all-out attack on Albert Card as though it was inviting him to sue them.

It concluded:

“The fact is, we believe, that Card isn’t worth two bob–intrinsically he isn’t worth a bean–and any money spent in attempting to recover damages from him would be simply money wasted. The only satisfaction that Mr. Blake is likely to have is the sympathy of the public and the support and confidence of his employers, and these he may be said to have gained in full measure.”

Even though Albert Card clearly wronged Blake, he could not have imagined such a public rebuke.

Within months Albert Card sailed back to England leaving Florence and Harold behind in Perth.

Running away

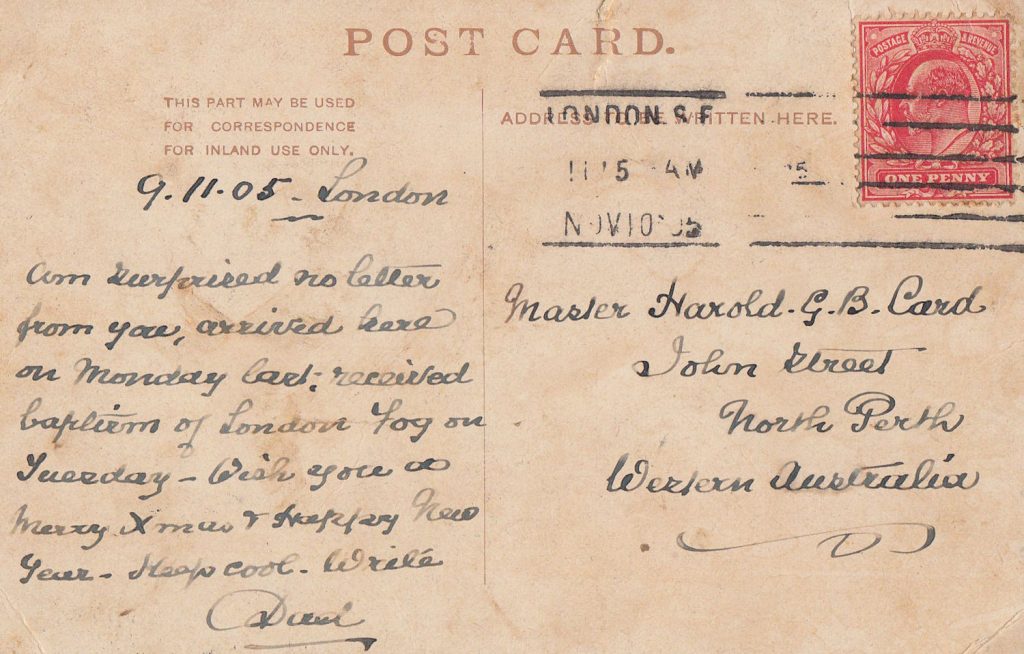

A postcard that Albert sent to his son Harold.

He was obviously ashamed of the effect his actions had on his family but his response of running away was also shameful.

However, it could also be seen as him sparing them from further shame. Either way, it was a horrible situation for both Florence and young Harold.

Harold was only 11 years old. What did his father tell him about why he was going to England alone?

Did Albert plan to send for Florence and Harold after he was established?

Albert Card had been well paid while employed as a town clerk. That suggests he could have left Florence and Harold well provided for, but later information shows that he did not.

He said he was going to bring his family to England when he was settled and, if that didn’t work out, he would return to Perth.

Albert regularly wrote to Florence for two years. And then the letters stopped.

It was obvious to Florence that her husband was not coming back to Perth, or sending for her and Harold to come to England.

Truth reveals home truths

Madame Montague image from Truth newspaper article. Reportedly Albert Card’s de facto wife, she was actually his niece, Annie Montague Powell, nee Card, and daughter of Albert’s brother Charles.

By 1912, when Florence went to court and divorced Albert, the scandalous nature of Albert Card’s life in England was published in the Truth newspaper.

Albert had established himself as a phrenologist and was apparently operating alongside one Madame Montague.

Evidence presented to the court showed that Albert and his lady friend were living as man and wife. Photographs of the duo appeared with the article.

The affidavits presented to the court and prepared by a law clerk named Jarman, were obviously influenced by Albert Card himself.

The article also rehashed some of Albert Card’s eccentricities from his time in Perth. Card, it said, was “always capable of making a tremendous lot of noise about very little”.

And: “Albert Card will be well remembered as a pushful sort of customer, who was at one time an official for the North Perth municipality, a voluminous letter-writer to the press, and a gas-bag upon political and municipal matters generally.”

The court was also told of a letter that Card had sent to Florence’s legal representative, Mr Durston. Card told Durston to go ahead with the case, as he did not intend to defend it. He also wrote that he would “wipe the floor with Mr Durston one of these days”.

The Truth article also observed:

… it was stated that Card and “Madam Montague” were living together as man and wife. Mr Durston also put in a letter he had received from Card, bearing on the divorce, which came to hand some weeks after the papers had been served. In it he waxes sarcastic at Mr. Durston’s expense, in the same old Albert Card style…

The article also included information from a English newspaper advertising Albert Card’s services. This and the photographs must have come from court records and were most likely provided by Mr Durston.

Divorce discussed

A separate report of the case reads thus:

DISSOLUTION OF MARRIAGE

ADULTERY AND DESERTION. Perth, March 12. Albert Card, for some time town clerk at North Perth; was the respondent in a divorce suit which was heard in the Supreme Court this morning before the Chief Justice. Emily Florence Card was the petitioner. The evidence showed that in 1905 Albert Card left for England. He corresponded with his wife regularly for two years, and then remained silent. It was learned afterwards that he was living in London with a woman who figured as Madame Montague, in the business of phrenologists and hand-readers, which she and Card carried on. His Honour said that adultery and desertion had been proved, and there would be a dissolution of marriage. The order nisi was made returnable in three months.

DISSOLUTION OF MARRIAGE. (1912, March 19). Kalgoorlie Western Argus (WA : 1896-1916), p. 41. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article33405561

A columnist from The Sunday Times added some colourful and unflattering observations on the Card divorce. The writer presupposed that Card was going to marry Madame Montague and quipped:

But we should advise “Madame Montague” to look well to the money as well as the marriage certificate, otherwise her queer Card may take it into his head to deprive her of both.

Phrenology ‘professor’

From the evidence of the divorce proceedings, a couple of facts are worth noting: (a) that he wrote to Florence for two years and then the letters stopped. And (b) that he was living with a Madame Montague; and they both were phrenologists and hand-readers.

The identity of Madame Montague is a question that needs further investigation.

There is an obvious clue on the 1911 census for 99 Selhurst Rd, South Norwood, Croydon, Surrey.

Those in the household were:

Annie Montague POWELL, Head, Widow, F, 46, Clairvoyant And Chierosophist, born Croydon, Surrey

Albert CARD, Uncle, Married 29 years, M, 59, Phrenologist And Chierosophist, born Tunbridge Wells, Kent

Rhoda CARD, Mother, Widow, F, 76, Old Age Pensioner, born Chalfront, Bucks

Edith Emily CARD, Cousin, Single, F, 26, Chierosophist And Phrenologist, born Croydon, Surrey

Annie Montague Powell was a daughter of Albert Card’s brother Charles.

That is established from the 1891 census for 84 Southbridge Rd, Croydon, not far from Selhurst Rd.

Those on the census were:

Charles CARD, Head, Married, M, 47, Decorater, born Tunbridge Wells, Kent

Roda CARD, Wife, Married, F, 52, born Chalfont, Buckinghamshire

Annie Montague CARD, Daughter, Single, F, 25, Exhibitors Assistant, born Croydon, Surrey

Edith Emily CARD, Daughter*, Single, F, 7, Scholar, born Croydon, Surrey

James POWELL, Visitor, Single, M, 25, Iron Mongers Assistant, born Peplow, Shropshire

*Edith Emily Card is actually Charles Card’s niece, the daughter of his brother Frederick and his wife Alice Skinner. Alice died in 1887 and Frederick remarried.

The James Powell on this census later married Annie Montague Card but died in 1904.

Madame Montague revealed

One of the many newspaper advertisements for Madam, or Madame, Montague.

Given that in 1911 Albert and his nieces were all involved in the same “caper” of phrenology and other activities such as hand-reading, there is no doubt that Annie Montague Powell (nee Card) and Madame Montague are the same person.

As well, there is only one clairvoyant on the 1911 census in Surrey (Annie Montague Powell). There are newspaper advertisements for a Madam Montague operating from 18 Northcote Rd, Croydon which is close to 99 Selhurst Rd, Croydon.

The trio continued in their “trade” (three-Card trick is more apt) advertising their services and fees widely.

Albert Card started calling himself Professor Card from as early as 1908.

An advertisement in The Merthyr Express, Aberdare and East Glamorgan Herald, Tredegar and West Monmouth Times of Saturday, 12 December 1908, reads:

“God has placed signs in the hands of all men, that every man may know his work.” Job xxxvii, 7.

Professor Albert Card, P.P.S.I., F.T.S.,

Phrenologist and Scientific Character Reader from the head, face or hands, may be consulted at the Cobden Temperance Hotel, 5 Pontmorglais, Merthy. Opening day Tuesday, 15th December instant, at 10.30 a.m. Fees from 1s, and 2s. 6d.

The “qualifications” (P.P.S.I., F.T.S.) would connect to the pseudo-scientific endeavour in which he was involved, mostly on Paignton Pier on the Devon coast near Torquay.

Albert Card’s prognostications separated gullible people from their money. Many other “practitioners” joined the money-making racket.

Perhaps Albert Card was convinced he had a gift, as many of his ilk do. While he operated mostly in Devon, Madam Montague is found mostly in Yorkshire and her native Surrey.

Another failed marriage

While plying his “trade” on Paignton Pier, Albert was attracted to a woman 30 years his junior. Her name was Ellen Jane Watson and she was a regular at the ladies’ swimming club for which she was secretary.

They took the train back to Albert’s home county, Surrey, where, surrounded by his family no doubt (perhaps his niece Madame Montague was there too), they married at the Croydon Registrar’s Office.

Albert Card marries Ellen Jane Watson at Croydon, Surrey. It’s intriguing to note that this was published within days of Albert appearing in court over his attempted suicide. Albert wanted the community to know of his situation and, perhaps, to reassure Ellen.

But, within months, there was a dramatic change in the relationship.

Court appearance Western Times 12 Jun 1919.

Albert attempted suicide on Paignton Pier:

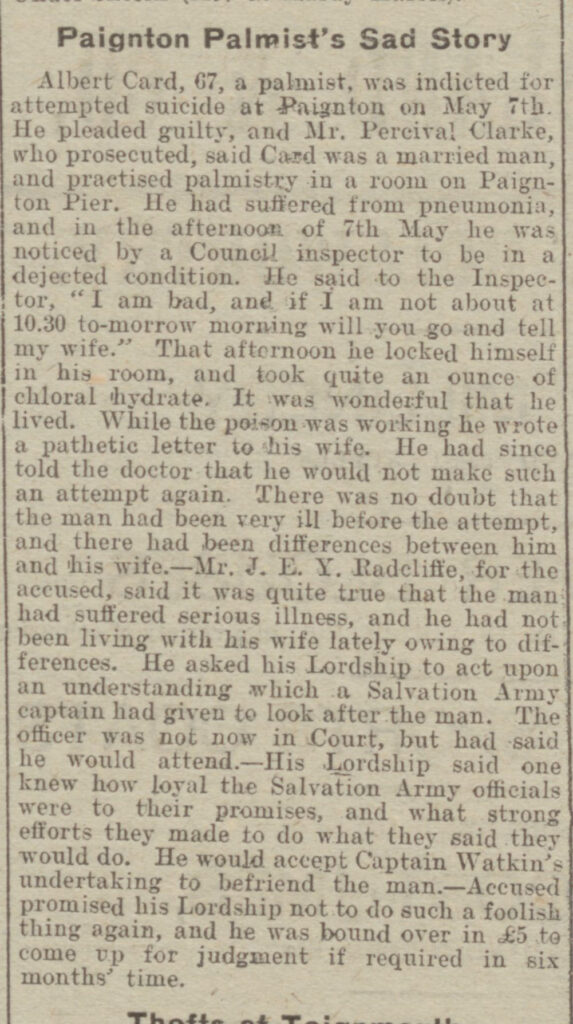

He faced court for his actions. A report read:

At Paignton Police Court on Friday, Albert Card, palmist on the Pier, was committed for trial to the Assizes, bail being refused, on a charge of attempted suicide.

Albert Card, a Paignton palmist, was committed for trial for attempted suicide on May 7th. The man had been ill, and told Beach Inspector Braund that if he was not about on Thursday morning to tell Mrs. Card. On Thursday morning he was not about and three constables going to his office on the pier found him lying there unconscious. He had taken poison. In his diary was a note. “Finish to-night”.

He later pleaded guilty and the Western Times of 12 June 1919 reported:

Albert Card, 67, a palmist, was indicted for attempted suicide at Paignton on May 7th. He pleaded guilty, and Mr Percival Clarke, who prosecuted, said Card was a married man, and practised palmistry in a room on Paignton Pier.

He had suffered from pneumonia, and in the afternoon of 7th May he was noticed by a Council inspector to be in a dejected condition.

He said to the Inspector, “I am bad, and if I am not about at 10.30 to-morrow morning will you go and tell my wife.”

That afternoon he locked himself in his room, and took quite an ounce of chloral hydrate.

It was wonderful that he lived.

While the poison was working he wrote a pathetic letter to his wife.

He had since told the doctor that he would not make such an attempt again.

There was no doubt that the man had been very ill before the attempt, and there had been differences between him and his wife.

Mr J.E.Y.Radcliffe, for the accused, said it was quite true that the man had suffered serious illness, and he had not been living with his wife lately owing to differences.

He asked his Lordship to act upon an understanding which a Salvation Army captain had given to look after the man.

The officer was not now in Court, but had said he would attend.

His Lordship said one knew how loyal the Salvation Army officials were to their promises, and what strong efforts they made to do what they said they would do.

He would accept Captain Watkin’s undertaking to befriend the man.

Accused promised his Lordship not do such a foolish thing again, and he was bound over in five pounds to come up for judgment if required in six months’ time.

Even though they’d been married barely six months, Albert only advertised the fact at the same time news of his suicide attempt became public.

We can’t know his motives, but it seems he desperately wanted to reassure his new wife of his commitment to her.

But did this work?

Son dies on battlefield

Albert Card’s suicide attempt came a few months after his only child, Harold, was killed in France, and that may have contributed to his actions. An account of Harold’s life is found here:

What of the second Mrs Card?

It seems that Ellen Jane then chose to live apart from Albert because by the 1921 census they are at different addresses. Ellen is lodging with one Elizabeth Watson (presumably there is some family connection between them) at 43 Park Road, St Marychurch, Torquay, Devon, while Albert is about 4 miles away at Paignton.

Note also that Ellen Jane is working as an assistant for her brother, Arthur H.Watson, outfitter, of Torquay.

The situation explains the confusing entries on Albert’s 1921 census record. “Married but no wife” is crossed out and “widowed” is written above his marital status.

Ellen and Albert did not divorce as by the 1939 register/census, she still describes herself as married. Likewise Albert is still married in 1939 but “living apart”. However, after Albert died in 1940, Ellen did remarry in 1943 to William Gibson.

Ellen died in 1962 at Torquay aged 81.

Florence hears of ‘suicide’

News of Albert’s suicide attempt reached Florence in Australia. By what method is unclear but one suspects Albert may have convinced someone to write to his ex-wife with false information that he was dead. Certainly Florence believed Albert had in fact died as is clear from a letter that she wrote in 1922 to the Australian Army.

Florence was answering a question from a Major McLean about Albert.

She wrote: “Some time ago you wrote asking me if my husband was alive. He committed suicide in England some twelve months ago. When my son left for the front he willed everything to me as my husband left Australia sixteen years ago and left both of us totally unprovided for.”

Again, Florence was convinced her husband was an adulterer by 1912, which was one of the grounds for divorce, and also that he was dead by 1922.

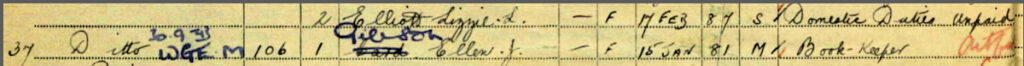

Albert on 1921 census

1921 census for Fairlie, Preston, Paignton, Devon, England.

Albert Card, Head, Male, 1850, 70, born Tunbridge Wells, Kent, England, Chierosophist & Phrenologist Own Account

Gerald Turner, Visitor, Male, 1887, 34, born Leeds, Yorkshire, England, Grocer Retired Own Account

Dorothy Mary Turner, Visitor, Female, 1893, 28, born Bradninch, Devon, England Domestic Duties

Note: There is an entry that indicates he conducted his “business” from the Paignton Pier.

Ellen Jane Card on 1921 census

Ellen Jane Card on 1921 census at Park Rd, Torquay.

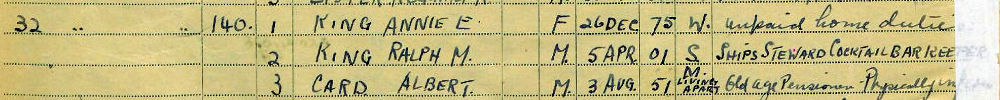

Albert on 1939 register/census

Albert Card on 1939 register boarding at 32 Shelley Crescent, Ealing, Southall, Middlesex

Ellen on 1939 register/census

Ellen Jane Card on 1939 register. Note official notation where Card surname is crossed out and Gibson written above. That indicates a later marriage.

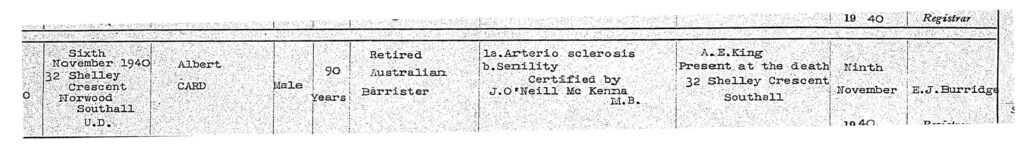

Albert’s death

Albert spent most of his last years offering his services from the Ealing house in which he boarded. The last known advertisement is from 1932 for his palmistry. He was no longer presenting himself as a phrenologist.

Albert Card advertisement from Buckingham Advertiser dated 8 Jan 1932.

A retired barrister!

His death entry confirms at least one thing about Albert Card’s character; that he had an unwavering belief in his ability and his perceived station in life.

It doesn’t reveal much about him (no parentage for example) but states his occupation as “retired Australian barrister”! Far from being a barrister, he was a junior law clerk who also qualified as a conveyancer.

Albert Card death entry. The informant was his landlady Annie King.

The excerpt reads:

6 Nov 1940, 32 Shelley Crescent, Norwood, Southall, Albert Card, male, 90* years, retired Australian barrister. Cause of death: Arterio sclerosis, senility. Informant A.E.King, present at the death.

*He was actually 89 when he died.

Fairly remembered?

Albert Card in 1912. Photo from Truth newspaper article.

The above observations about Albert Card’s life have been made with an eye to fairness. Even though he’s been dead since 1940, the man’s life should not be held up to ridicule.

If someone were to write a frank, no-holds barred appraisal of my life, it would be ugly reading in parts.

With that in mind, I have sought to be even-handed in my approach while not suppressing anything along the way.

A chance discovery led me to digging further into Albert’s life. Until late in 2024 I had believed that Albert Card had died by his own hand.

Albert Card made mistakes and eked out a living from a questionable activity. But I believe he did try to shield his wife Florence from having her name associated with his.

If that is the case, he deserves to be remembered for such a kindness as messy as the application of it may seem to those of us looking back.