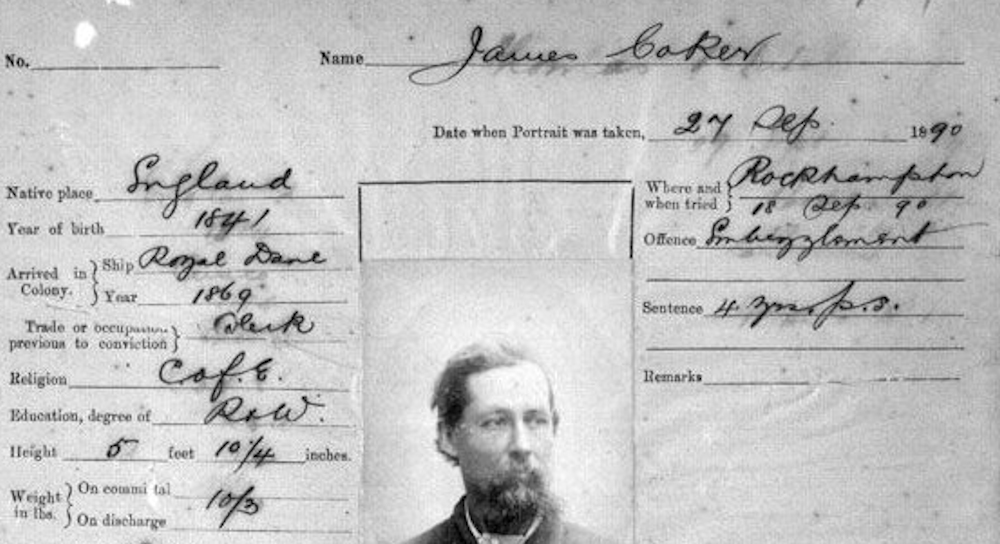

The prison record of a criminal who spent time in Queensland’s infamous St Helena Island jail is a stark reminder of how human nature can be corrupted.

This man, James Thomas Coker, embezzled money as a servant of a municipal authority. I am one of his many descendants.

What do you do with the information that someone who went before you carried out a serious crime – an abuse of trust – for years before being found out?

He made no attempt to deny his guilt when confronted with the accusations. That does not excuse his actions. You can’t hide from the facts, nor try to explain them way or even downplay the serious nature of the crime.

James Thomas Coker was my grandfather’s grandfather on my mother’s side. He was town clerk of the North Rockhampton Borough Council for about 20 years.

James Coker and his wife Emily Lee.

He was the third son of a successful businessman, William Coker, who was a ship’s chandler in Stepney, London, in the mid-1800s. When James was born in 1841, business was booming for the company run by his father and grandfather.

Business fails, money disappears

By 1852, both men were dead and the future was less certain. By 1867, the business was gone along with property and sums of money that William senior had left in his will to the six grandsons.

By July 1870, James had left England for Rockhampton, Queensland, Australia. It seems he came to fill the role of town clerk. In those times, the town had municipal authorities for both sides of the river.

When the Cokers arrived on the Royal Dane in November 1870, the family unit also included wife Emily and children Jane (11), Emily (9), Ada (7), Leonard (5), Arthur (4) and Henry (my grandfather’s father, aged 2).

Nine more children were born to the couple in the ensuing 15 years, but only James Martin, Albert Napier, Herbert Leslie and Archibald Lawson survived to adulthood.

Whether Coker honestly served the council at all is open to conjecture because, from 1886, he had a second set of books and was keeping money for himself.

An incident in 1888 should have shaken Coker out of his deceitful ways or at least caused authorities to have a closer look at the council. It came when the mayor, John Wallis Rutter, was jailed seven years for fraud.

At that time, Coker was in the thick of his scheme but auditors had not picked up on it.

It is often said criminals don’t stop until they get caught. That was certainly true in the case of James Thomas Coker.

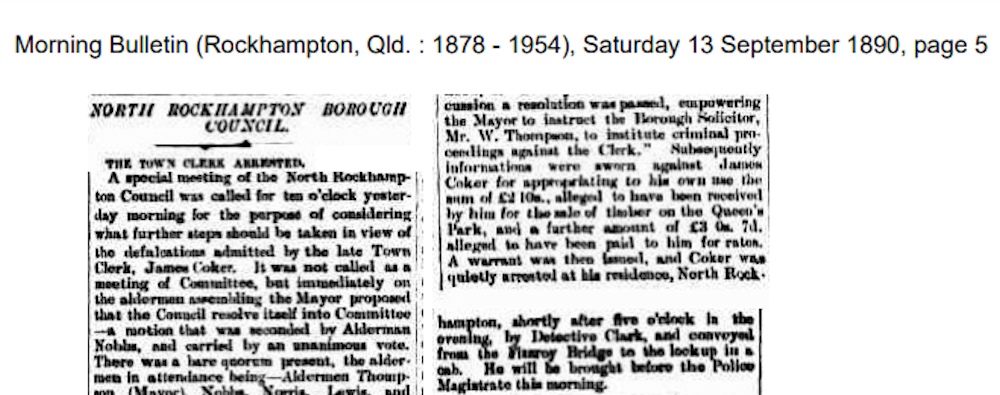

Morning Bulletin report of James Coker’s arrest.

Perhaps the seeds of doubt were growing in October 1888 when councillors discussed at length Coker’s claims that a third person other than he and the mayor had access to the strongroom.

Trying to cover his tracks

In July, Coker reported a burglary at the council offices during which the mayor’s room was entered, a quantity of spirits stolen and a valuable lamp broken.

The newspaper report of the meeting is somewhat disjointed but mentions Coker’s belief about a third key and, crucially to what transpired 18 months later, the disappearance of the butt of a receipt book he received from a committee chairman.

That was when Coker suggested the existence of a third key. Thereafter, the strongroom lock was changed. By August 1890, the pressure was building and, reading between the lines, perhaps the mayor and other alderman had firm suspicions about their town clerk.

A report in the Rockhampton Morning Bulletin newspaper on Saturday 2 August 1890, leaves the reader in little doubt that James Thomas Coker’s days were numbered.

Judgment day beckons

The paper reported a “mysterious silence” about the council’s finances which were supposed to be tabled at each fortnightly meeting. That had not been done for several months.

The paper’s closing observations are worth recounting verbatim:

“Only one conclusion can be come to after considering all the facts – that the Town Clerk has repeatedly disobeyed, the resolution of Council, and that the Mayor, if he has not approved of such a course of procedure, has shielded him from all blame. But why all this silence about the finances? Are they in such a bad way that His Worship does not care to have the facts published? The Council – and if no alderman has the courage then the ratepayers – should demand that the clandestine procedure be at once abandoned.”

State Library of Queensland image of St Helena prison taken in 1893 when James Coker was an inmate.

A fortnight later, the paper again reported on Coker’s objections to anyone else handling the rates books. The report reads:

“The meeting of the North Rockhampton Council on Wednesday was rather lengthy, a good deal of time being wasted in discussing a motion introduced by Alderman Noble.

That councillor, with a view to setting the finances to rights, brought forward a proposal instructing the Town Clerk to make out a copy of the rates in arrears, the copy to be given to the junior in the office, the latter to have the power of receiving money tendered in payment.

The reason for this appears to be that the Town Clerk is understood to be averse to anyone touching the books in his absence. On the face of it the idea was a good one, but then there is no reason, so far as we can see, why another official besides the Town Clerk should not have access to the books.

It may be, as Alderman Nobbs said, that Mr Coker does not care for anyone to interfere, but that gentleman’s wishes in the matter should not be allowed to operate prejudicially to the interests of the Council. Of course he cannot always be in the office – it would be unreasonable to expect it; but it is equally unreasonable for Mr Coker to imagine that ratepayers are going to call time after time with their money.

If he is obstinate in the matter, and no other conclusion can be come to after reading Alderman Nobbs’s remarks, it was manifestly the duty of the alderman named, to have said so straight out. The half-yearly statement of receipts and expenditure, was laid on the table, and will no doubt be published in a few days.

The Mayor has promised that now the accounts have been brought up to date a report of the state of the finances shall be laid on the table at each meeting.”

About six weeks later, James Thomas Coker was arrested for embezzlement and admitted to having a second set of books on which he issued receipts for moneys received.

The former North Rockhampton Borough Council Building pictured in 2018.

Full admission and restitution

He said he took about £450 and it emerged his actions started about four years earlier. Coker handed over a list of the sums misappropriated and also a number of butts from receipt books.

Justice was swift in those days and by 18 September 1890, Coker had received a four-year sentence, to be served on the infamous St Helena Island in the mouth of the Brisbane River.

It was 21 October when prisoner No.3802 arrived on St Helena and assigned to cell No.283. It was to be his home until 17 October 1893 when he was released on three months “special remission”.

In the record of his time there, Coker was twice cautioned for “offences”. The first was having in his possession a lead pencil and a bag of chillies. The second was for insolence.

His physical description was dark complexion, 5ft 10¼in tall, medium build, brown hair and brown eyes.

Coker’s former mayor John Rutter was also on St Helena. He had been in cell No. 51 since February 1888 and was not due for release until September 1893.

Petition for early release

Arthur Coker, who was known as Shorty.

Eighteen months after he was sentenced, Coker’s wife Emily submitted a petition for his early release.

In the meantime, Emily supported herself and her youngest children as a nurse/midwife.

When he did get out of prison, James Coker returned to Rockhampton, eventually setting up as a land agent.

The Coker name was again associated with the council when his son Arthur (1867-1945) was elected an alderman in 1903.

Around 1904, it seems James and Emily decided to part ways as she moved to Perth, Western Australia, apparently to live with their eldest daughter Jane.

The two youngest sons, Herbert and Archibald, followed her out of Queensland. Herbert was last heard of in Kalgoorlie, Western Australia, while Archibald saw out his days in Victoria.

FOOTNOTE: The author, Warren Nunn, started his journalism career at The Rockhampton Morning Bulletin on 3 July 1972.

© The material on this page is the sole work of the author.