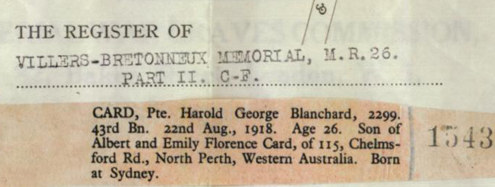

On 22 August 1918, Harold Card’s short, drama-filled life ended when a German shell burst near the village of Etinehem in the Villers-Bretonneux region of France, not far from the Somme.

Just like millions of other young men who had needlessly died on battlefields in the course of human history, Harold never lived to realise his potential; he did not marry, raise a family or build a career.

He came into the world in March 1892 in what is now known as the North Shore area of Sydney, Australia’s biggest city.

He was the son of an English-born couple, Albert Card and Emily Florence Coker who married in 1882 at Westwood, near Rockhampton, Queensland, Australia where Florence—she was known by her second name—grew up after her parents brought their young family out to Australia in 1870.

About a year before they married, Florence had a male child she named Francis Coker who only lived for a few weeks.

It seems possible—although it’s not known for sure—that Albert may have been that child’s father given they married 14 months later.

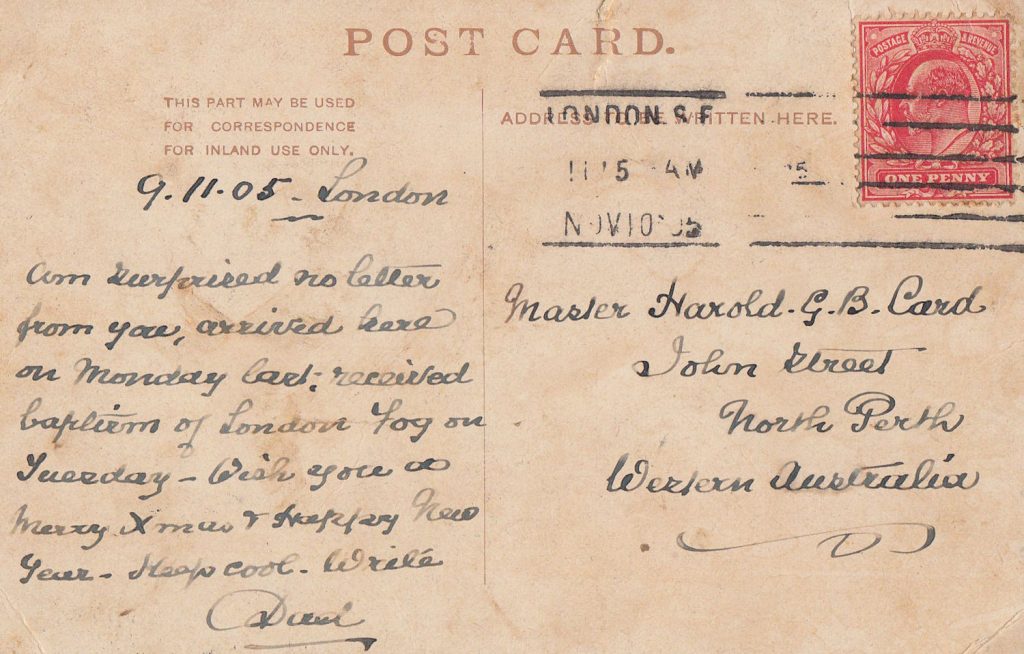

A postcard that Harold Card received from his father, Albert, in 1905 after he went to London, leaving behind his wife and teenage son. The other side of the card includes an image of Albert.

At some point thereafter, Albert and Florence moved to Sydney in New South Wales because that’s where Harold was born a decade later. Given Florence had already given birth to a child; it seems she must have had issues having children because of Harold’s arrival 10 years into the marriage.

The Cards next moved to Perth, Western Australia around the turn of the century because they are found on electoral records in 1903 where Albert is described as a conveyancer.

Beery, bungling, blackguard

Albert Card had been secretary of the North Perth Roads Board as well as having been the North Perth municipality’s town clerk but he appears to have been anything but competent in that job because in 1904 The Sunday Times newspaper had an article which highlighted his questionable actions.

It is titled: Currish, Card, a beery, bungling, blackguard.

In hindsight, it is easy to see the man was emotionally unstable.

Publicly disgraced, Albert abandoned his family and left to live in England. More details of that can be found here, including that he took his own life in 1921.

In November 1905, Albert did send Harold a card from London with the words:

“Am surprised no letter from you, arrived here on Monday last; received baptism from London fog on Tuesday-wish you a merry xmas and happy new year-keep cool-write. Dad”

Such correspondence must have been emotionally confusing for a 13-year-old boy trying to come to terms with his dad leaving the family home and going to the other side of the world along with all the horrible things being said about him.

Cross-country move

Florence’s mother Emily Coker (nee Lee) left her husband James Thomas Coker in Rockhampton about 1904 and travelled across to the other side of Australia and joined her daughter in Perth.

They lived only a handful of streets from each other and it’s certain that young Harold had both his mother’s and grandmother’s influence to counteract the trauma of having been abandoned by his father.

Before Harold was born, his grandfather James Thomas Coker had been jailed for fraud, so there is little evidence of a lasting, positive male influence on his life, and there is no surprise that Emily left James and headed west to Perth.

Harold signs up for service.

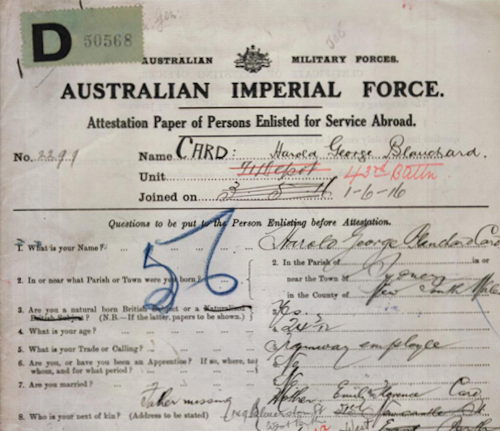

In 1916, when Harold signed up to fight in WW1, he was employed on Perth’s tramway network which had only been established in 1899.

Without sighting his employment record—which could be available in the government archives—it’s not known what role young Harold had.

There are about 50 pages in Harold’s service record starting with his sign-up form dated 1 June 1916. It gives his mother’s address as 149 Palmerston St, East Perth, which is only a few minutes’ walk from a previous address, 515 Newcastle St, East Perth (that part of the street is now a small business centre), which has been crossed out on the form.

There is also a sober entry “Father missing”.

What the form also reveals is that Harold had previously been rejected for service because he had undergone an operation for varicose veins, which seems an odd condition for someone in their early 20s.

On this occasion, though, No 2299 Harold George Blanchard Card was deemed fit for military service and assigned to the 43rd Battalion. By October he boarded a ship at Fremantle that first went to Melbourne before heading to France via England.

He was described as 5ft 10ins (1.78m) tall, weighed 153 pounds (about 70kg), had hazel eyes, light brown hair and he had a scar on his right leg (perhaps from his operation).

Wounded in action

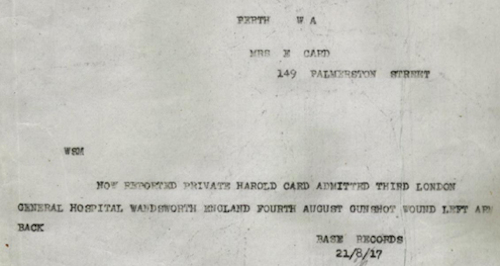

In March 1917, Harold first saw action and in August received a gunshot wound to his back and both arms. One can only image how anxious his mother was when she received this bland telegram a few days later:

Reported private Harold Card wounded will advise anything further received.

That was followed by a second telegram:

Not reported private Harold Card admitted Third London General Hospital Wandsworth England fourth August gunshot wound left arm back.

Unwelcome news.

The wound must not have been too serious because there is a note that it had healed by 14 September, so Harold was sent to the training area at Hurdcott in Wiltshire where was he stationed for several weeks before being sent back to France in November.

He was at Rouelles (24 November 1917), Saint-Omer (28 March 1918), Boulogne (8 April 1918), Havre (18 April 1918) and then in the Villers-Bretonneux region where he was killed in August.

As was the case with countless other soldiers on that dreadful arena of war, Harold had several bouts of diarrhoea.

Gallant, dedicated soldier

There are two letters giving background to Harold’s service in France. He was a runner which meant he had the task of getting vital information to headquarters or other units and would have been at risk from snipers, stray bullets and shells, etc.

A letter from Lt. A.H.Dalziel, sent from 3rd London General Hospital and 12 September 1918 reads:

Dear Madam. Your letter of 24th Sep. just to hand in which you ask for information re the late Pvte. Harold Card. As I was doing duty with another company of that particular day, I was not actually with him when he was killed, but if you write to the O/C “A” Coy 43rd Btl (Captain J.J.Moran) he will give you more information that I can as to the place and nature of his death. Speaking of Harold as a man and a soldier, I can say this (and for a long time he was continually with me, being my runner); as a man he was straight and good living and liked by all, and as a soldier he was always ready and fearless in his duty. When the occasion arose, and it was necessary to get information sent back to headquarters, no matter what the risk, I always knew that so long as he could move the information would arrive where it was required. And no soldier can show greater devotion to his duty than to place it before his own life, and this Harold was always prepared to do. His death was a loss to the whole company, and I am sorry that I cannot give you the exact locality of his grave, but I am sure Capt. Morgan will give you all the information in that respect. His death was instantaneous. In conclusion, please allow me to express for myself and his comrades in the company, our deepest sympathy for you all to whom he was so dear. Yours sincerely, A.H.Dalziel, Lt.

It was common for the military to write that “his death was instantaneous” because it was felt it would be too much for the family to read that their son had suffered painfully for hours or days.

It’s easy to conclude from the above narrative that the phrase was added for such a purpose because it doesn’t fit otherwise.

A lieutenant in Harold’s battalion also wrote to Florence:

Dear Madam, Returning health permits me to perform a duty which I feel is long overdue. Doubtless you have been already notified of your son’s death in action on August 22nd. On that day, the 43rd Battalion was advancing to attack near the town of Bray (Bray-sur-Somme), north of the Somme. We were being heavily shelled, for we were under the observation of the enemy. At about 7 o’clock in the morning a large shell burst among the section to which Pte Card was attached and he fell with a hopeless wound to the groin, dying almost at once. Three others of the section were killed and three wounded. Unfortunately, I was myself wounded at this time and so cannot say exactly where your son was buried; but the cemetery will probably be very near the spot where he and so many of his comrades fell that day. That is near a cross roads just half a mile north of Etinehem, now far behind our lines and out of range of all German shells. Pte Card was a good and brave soldier, esteemed by both officers and men throughout the Battalion, and one and all. We wish as we may to express our great sympathy with you in your sad loss. And yet we believe he fell, as all brave men wish, advancing in the face of the enemy. Frank W. Thomas, Lieut., 3 Platoon, “A” Coy, 43rd Btn. A.I.F

From the above, the first letter gives no details of Harold’s death but Lieutenant Dalziel’s describes Harold as a soldier who did sterling service as a runner.

Official recognition.

In the second letter, Lieutenant Thomas describes the battalion advancing on the town of Bray-sur-Somme which is only about 3km from Etinehem when a shell-burst killed Harold and some others.

Harold was buried about 2000 yards (1.8km) from Bray-sur-Somme but the co-ordinates in his record don’t match normal longitude and latitude.

Treasured possessions

Harold was an exemplary soldier and the only “blemish” on his record was a minor disciplinary incident in England over burning a naked light after lights-out.

For Florence, the grief must have been unbearable and she treasured the return of his possessions as well as medals and other honours.

In 1919, Florence was sent her son’s effects that included a pipe, devotional book, a compass, a money belt, a woollen cap comforter, tobacco pouch, letters, a card photo, and a German machine gun belt.

In 1922, Florence received a memorial scroll, as well as a British war medal and a Victory medal.

Florence also had a memorial card printed that has an image of Harold in uniform with the words: In loving memory of my dear son Harold G.B.Card 43rd Battalion killed in action “somewhere in France” August 22nd, 1918, aged 26 years 5 months.

It also had the following verse:

They have laid our son down to rest

In the flag with the Southern Cross,

And we mourn for him as one of the best,

For his death was Australia’s loss.

He has sailed on his last commission

To that beautiful place called rest,

And his head is gently pillowed

On the Great Commander’s breast.

Deeply mourned –

Inserted by his loving mother.

Note: I am a first cousin, twice removed of Harold Card who was a first cousin of my maternal grandfather. See the relationship: http://tinyurl.com/gwvqoy5

©Warren Nunn (First published 14 Jan 2017)