A short, tragic life

Napoleon Nunn, who was born in 1831 to an unmarried mother in Chevington, Suffolk, lived an eventful, tragic life and died young.

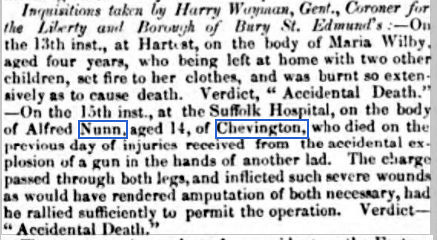

Report of the inquest into Alfred Nunn’s accidental death that cleared Napoleon Nunn of any wrongdoing.

Napoleon was obviously named for the French revolutionary Napoleon Bonaparte.

His young mum must have imagined a grand existence for her child and could not have known how much pain and confusion would befall her son.

As is the case with countless young women who’ve fallen pregnant, Naomi was left to deal with raising a child in difficult circumstances.

It seems she may have had little involvement given that a later incident shows he was raised by his grandfather.

In 1843 when aged 12, Napoleon was holding a gun that exploded and wounded and killed a distant cousin named Alfred Nunn.

Young Napoleon was cleared of being responsible for the accident.

[Note: Alfred Nunn was my great-great grandfather‘s brother. This is how I relate to him as a third great grand-nephew and a third cousin four times removed.]

However, there followed a public exchange which cast aspersions on the family as well as Chevington’s faithful rector, Rev John White and the church in general.

Someone wanted to apportion blame on others for an unfortunate accident involving four boys aged 10, 12, 13 and 14, playing with a gun.

Unfortunate letter

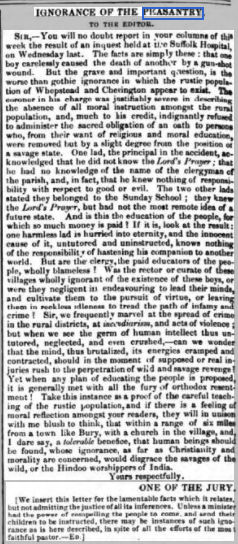

The ill-informed letter that caused the Nunn family so much heartache.

The letter writer, who signed as “one of the jury”, was ill-informed, unthinking and, while purporting to represent a Christian response, showed a gross lack of understanding.

Blaming the church and calling a 12-year-old boy an ignorant peasant is not at all helpful.

A transcript of the letter to the Bury and Norwich Post, published 22 Nov 1843, follows:

Ignorance of the peasantry.

To the Editor.

Sir, – You will no doubt report in your columns of this week the result of an inquest held at the Suffolk Hospital on Wednesday last. The facts are simply these: that one boy carelessly caused the death of another boy by a gun-shot wound.

But the grave and important question is the worse than gothic ignorance in which the rustic population of Whepstead and Chevington appear to exist.

The coroner in his charge was justifiably severe in describing the absence of all moral instruction were removed but by a slight degree from the position of a savage state.

One lad, the principal in the accident, acknowledged that he did not know the Lord’s Prayer; that he had no knowledge of the name of the clergyman of the parish, and, in fact, that he knew nothing of responsibility with respect to good or evil.

The two other lads stated they belonged to the Sunday School; they knew the Lord’s Prayer, but had not the most remote idea of a future state.

And is this the education of the people, for which so much money is paid? If it is, look at the result; one harmless lad is hurried into eternity, and the innocent cause of it; untutored and uninstructed, knows nothing of the responsibility of hastening his companion to another world.

But are the clergy, the paid educators of the people, wholly blameless? Was the rector or curate of these villages wholly ignorant of the existence of these boys, or were they negligent in endeavouring to lead their minds and cultivate them to the pursuit of virtue, or leaving them in reckless idleness to tread the path of infamy and crime?

Sir, we frequently marvel at the spread of crime in the rural districts, at incendiarism, and acts of violence; but when we see the germ of human intellect thus untutored, neglected, and even crushed? Can we wonder that the mind, thus brutalized, its energies cramped and contracted, should in the moment of supposed or real injuries rush to the perpetration of wild and savage revenge?

Yet when any plan of educating the people is proposed, it is generally met with all the fury of orthodox resentment? Take this instance of proof of the careful teaching of the rustic population, and it there is a feeling of moral reflection amongst your readers, they will in unison with me blush to think, that within a range of six miles from a town like Bury, with a church in the village, and, I dare say, a tolerable benefice, that human beings should be found, whose ignorance, as far as Christianity and morality are concerned, would disgrace the savages of the wild, or the Hindoo worshippers in India.

Yours respectfully, One of the Jury.

[We insert this letter for the lamentable facts which it relates, but not admitting the justice of all its inferences. Unless a minister had the power of compelling the people to come, and send their children to be instructed, there may be instances of such ignorance as is here described, in spite of all the efforts of the most faithful pastor.]

Considered response

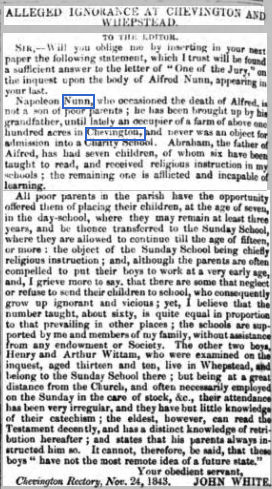

Rev John White’s letter defending Napoleon Nunn, his family, and his community.

The ill-tempered letter brought a considered and far more Christian response from Rev White.

The transcript of the letter follows:

Alleged ignorance at Chevington and Whepstead. To the editor.

Sir, – Will you oblige me by inserting in your next paper the following statement, which I trust will be found a sufficient answer to the letter of “One of the Jury,” on the inquest upon the body of Alfred Nunn, appearing in your last.

Napoleon Nunn, who occasioned the death of Alfred, is not a son of poor parents; he has been brought up by his grandfather, until lately an occupier of a farm of above hundred acres in Chevington, and never was an object for admission into a Charity School.

Abraham, the father of Alfred, has had seven children, of whom six have been taught to read, and received religious instruction in my schools; the remaining one is afflicted and incapable of learning.

All poor parents in the parish have the opportunity offered them of placing their children, at the age of seven, in the day-school, where they may remain at least three years, and be thence transferred to the Sunday School, where they are allowed to continue till the age of fifteen, or more: the object of the Sunday School being chiefly religious instruction; and, although the parents are often compelled to put their boys to work at a very early age, and, I grieve more to say, that there are some that neglect or refuse to send their children to school, who consequently grow up ignorant and vicious; yet, I believe that the number taught, about sixty, is quite equal in proportion to that prevailing in other places; the schools are supported by me and members of my family, without assistance from any endowment or Society.

The other two boys, Henry and Arthur Wittam, who were examined on the inquest, aged thirteen and ten, live in Whepstead, and belong to the Sunday School there; but being at a great distance from the church, and often necessarily employed on the Sunday in the care of stock, &c., their attendance has been very irregular, and they have but little knowledge of their catechisms; the eldest, however, can read the Testament decently, and has a distinct knowledge of retribution hereafter; and stated that his parents always instructed him so. It cannot, therefore, be said, that these boys “have not the remote idea of a future state.” Your obedient servant, John White, Chevington Rectory, Nov.24, 1843.

Troubled individual

Without going too deeply into the details of the responses, it’s obvious that Napoleon was a confused and broken young man despite his grandfather’s efforts.

Within five years of the shooting incident, Napoleon’s grandfather, John Nunn, passed away and he is thereafter found on the March 1851 census at the Pear Tree Inn, Whepstead, as a brewer in the establishment that his grandmother was running. She seems to have died within weeks and Napoleon took over as landlord.

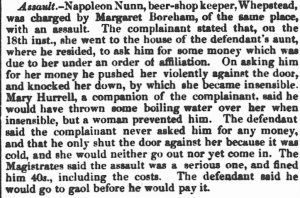

Napoleon is described as beer-shop keeper, of Whepstead, in another incident in 1852 when he was convicted of assaulting Margaret Boreham at Whepstead.

He had fathered a child with Margaret and was under an order of affiliation. Napoleon had not met his responsibilities and, when Margaret Boreham confronted him, he reacted violently.

Assault conviction

Bury and Norwich Post report of Napoleon Nunn assault case published 1 Dec 1852.

A transcript of a report of the incident in the Bury and Norwich Post of 1 Dec 1852 follows:

Assault. – Napoleon Nunn, beer-shop keeper, Whepstead, was charged by Margaret Boreham, of the same place, with an assault. The complainant stated that, on the 18th inst., she went to the house of the defendant’s aunt, where he resided, to ask him for some money which was due to her under an order of affiliation.

On asking him for her money he pushed her violently against the door, and knocked her down, by which she became insensible. Mary Hurrell, a companion of the complainant, said he would have thrown some boiling water over her when insensible, but a woman prevented him.

The defendant said the complainant never asked him for any money, and that he only shut the door against her because it was cold, and she would neither go out nor yet come in. The Magistrates said the assault was a serious one, and fined him 40s., including the costs. The defendant said he would go to goal before he would pay it.

Other children?

On the basis that Napoleon was father to Margaret’s child, further research shows she had three sons; Ephraim (aged 4 in 1851), Amos (aged 7 months in March 1851) and Napoleon.

So, we can say with some certainty that the Napoleon Boreham baptised 17 Oct 1852 at Whepstead, was Napoleon Nunn’s child (see following baptism transcript).

Suffolk Baptism Index 1538-1911 Napoleon Boreham Baptism date 17 Oct 1852 Parish Whepstead, St Petronilla Relationship Son Father’s first name(s)- Mothers first name(s) Margaret Bb. Sp County Suffolk

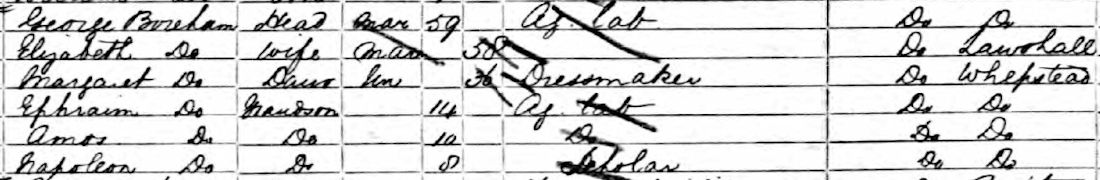

On the 1851 census, Margaret Boreham is at Whepstead with her parents. She is aged 27, unmarried, and her sons, Ephraim and Amos are also in the household.

Given the incident in which Margaret was assaulted happened in December 1852, it occurred within several weeks of when Napoleon was baptised. Napoleon Boreham also had a short life and died in 1869.

There’s little doubt of Napoleon Nunn’s involvement with Margaret Boreham and it seems reasonable to assume he could have also fathered either Ephraim or Amos.

Margaret Boreham with her parents on the 1861 census and her three sons Ephraim, Amos and Napoleon.

Napoleon Nunn marries

However, Napoleon Nunn did not (unsurprisingly) continue his relationship with Margaret Boreham and married Mahala Rutter in 1854 but passed away the following year aged only 24. They do not appear to have had any children.

His was a short, drama-filled life.

The parish record shows that Napoleon was the base child of Naomi Nunn whose family can be traced back to William Nunn, son of William Nunn and Ann Fenn.

This William Nunn died in Chevington in 1805, and there a couple of candidates for his father, also named William. Given the Chevington connection, he’s likely to be the son (or grandson) of this William Nunn.

It seems that Naomi had little or no involvement with raising Napoleon. Naomi married Thomas Rolfe, with whom she had at least one child, and lived to 95.

So many people have had similar experiences to Napoleon Nunn. A constant theme is adults making mistakes and their offspring making similar decisions.

Nothing has changed over the centuries.