IT was a scandal at the time that involved a number of men including several gold miners and two rather inept thugs who ended up in jail.

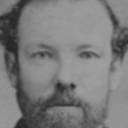

Henry Aldridge aged about 80.

The drama unfolded on Thursday, July 30, 1868, when William Troden and Joseph Blake first held up a lone rider three miles from Imbil in Queensland, Australia.

They took from the 24-year-old man, Henry Aldridge, five shillings and twopence, a pair of boots and a hat, leaving him naked and tied to a sapling.

Troden, who went by the alias Podgy, let slip the handkerchief that concealed his features and Aldridge got a good look at the face of a stocky, older man with a gruff voice who had struck him.

The previous morning, Imbil Station manager Captain Robert Hickson had passed Troden and Blake on the Gympie-Imbil road.

Capt Hickson had been heading to Gympie but his horse broke away and went back to the station. As he chased the horse, Capt Hickson again came face to face with the duo. He was able to give a detailed description of the men, their horses and the weapons they were carrying.

Crucial evidence

All this proved crucial evidence when Troden and Blake faced Maryborough Circuit Court on September 26 charged with robbery under arms.

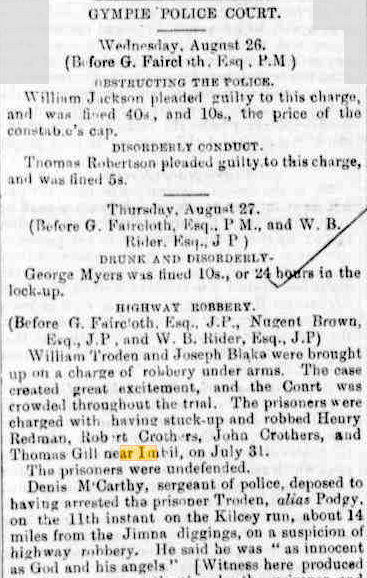

Excerpt of Police Court hearing that appeared in The Nashville Times, Gympie and Mary River Mining Gazette, 29 August 1868, p.3.

Despite their encounters with Capt Hickson and the relatively unproductive robbery of Aldridge, Troden and Blake were desperate enough to try another stick-up.

Between four and five o’clock, Edwin Redman, Thomas Gill and brothers Robert and John Crothers were confronted and robbed within miles of where Aldridge sat trussed up to a tree.

Although the bushrangers tried to conceal their faces, it was to be their horses, voices, weapons, manner and riding styles that would give them away.

Edwin Redman was a jockey and his keen observations about both horse and rider were later to be recounted in the Circuit Court. He was also to testify that he saw Troden’s uncovered face from a distance as Blake held the men at gunpoint.

Troden and Blake tied the four men two by two, took 26 shillings from Redman and 1 pound 12 and sixpence from John Crothers.

Crothers and Redman were lashed together but it was to be Thomas Gill who first loosed his bindings aided by the fact his was missing the middle finger on one hand.

Lashed to sapling

While this was happening, Aldridge was having a far more difficult time. It took him until the next morning to get clear of the sapling.

He must have been lashed to it around the chest because he gave evidence that his hands and feet were still bound when he struggled back through the thick bush to the road.

Henry Aldridge aged about 43.

Aldridge wrote 50-odd years later:

“At last I got in sight of the road, when I saw four men with swags going towards Gympie.

When I coo-ed to them they seemed to hesitate about coming on to me, as I was naked and covered in blood and dirt from head to foot.

When they cut the string that bound my wrists and ankles, I must have swooned away (for) when I came to they was giving me a drink of water and they found me some clothes after washing me in the creek to which they had carried me.

These same four men had been stuck-up and robbed the night before.”

The five men obviously talked about their encounters, sharing information that no doubt convinced them that the same bandits had accosted them.

After Jimna police sergeant Denis McCarthy gathered evidence from all parties, a picture emerged about the bushrangers, and, as a bonus, Aldridge was able to positively identify Troden from images police showed him.

When McCarthy arrested Troden on August 11, he was wearing Aldridge’s boots and, 11 days later when he arrested Blake, he got an interesting reaction from the prisoner.

Dodgy Podgy

Image of William Troden taken from his prison record in Queensland.

In his statement to the Gympie Police Court on August 27, McCarthy gave evidence that Blake had said: “I was told by one of the station men to have nothing to do with Podgy (Troden). I thought he was only gammon but I am sorry I did not take his advice.”

Aided by another person, McCarthy found a double-barrel gun secreted in a log near Blake’s tent at “the foot of the dividing range of the Brisbane and Mary waters”. Blake let it be known that it was his mate’s (Troden’s) gun.

As he was later to testify to the Maryborough Circuit Court, Redman told the lower court he recognised the horses as the ones the bushrangers had been riding when he and his mates were held up.

The Police Court hearing offered an acceptable case to be put to the Maryborough Circuit Court sittings. The case received almost three columns of coverage in The Brisbane Courier newspaper.

Damaging cross-examination

The account read in part: “Prisoners were not defended by counsel, but occupied the time of the court in examining the several witnesses, sometimes very ingeniously, and sometimes with damaging effect to their own case.”

Capt Hickson and Edwin Redman’s evidence agreed on the individuals, their horses and even the way in which they sat in the saddle.

Capt Hickson said Troden “rode very short, as if he could not ride; he rode very loose and bent down”.

Part of their defence was Troden’s questioning of his co-defendant, Blake. They presented evidence between them that Troden did not have a horse and that others had seen them elsewhere on the day they were supposed to have conducted the stick-ups.

Blake did not deny ownership of the horse identified by the victims but said it had been “loaned out on hire”.

His Honour, the Chief Justice, Sir James Cockle, spent three hours summing up; the jury took about 30 minutes to reach a guilty verdict.

Portrait of Sir James Cockle from National Library of Australia.

Hanging option

In passing sentence, Sir James said if the accused had wounded any of the victims with the firearms, the penalty would have been hanging.

He said: “If any blow had been given they should have received blow for blow; but they had struck no blow; yet they had committed a most cruel act, and the language the Crown Prosecutor had used in describing it was not a bit too strong. It was a most cruel act to bind these men, so that they would in all probability be exposed in the bush all night, and, it might be, to most serious injury – if not death.”

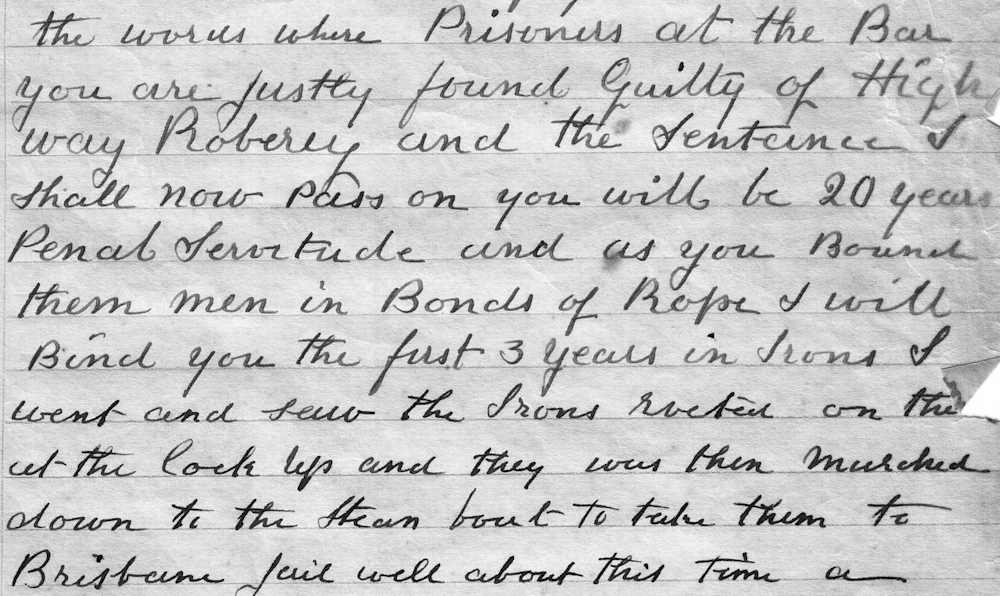

The report continued: “They had bound their victims with rope; he would have them bound in return in fetters of iron. The sentence of the Court was 20 years penal servitude; the first three years in irons.”

Henry Aldridge had his own slant on proceedings. He had waited patiently to give his evidence but the Crown had no need to proceed on the separate matter as iron-clad as the case was.

Maybe Aldridge embellished the story a bit when he wrote:

“The judge looked over at the prisoners and told them that it was lucky for them that they was not on trial for the other case that was mine.

“So he started to pass sentence on them. I shall never forget his words.

The words were: ‘Prisoners at the bar, you are justly found guilty of highway robbery and the sentence I shall now pass on you will be 20 years penal servitude and as you bound them in bonds of rope, I will bind you the first three years in irons’.

I went and saw the irons riveted on them at the lock-up and they was then marched down to the steamboat to take them to the Brisbane jail.”

Aldridge did not record what happened that night but chances are there was a significant celebration in one of Maryborough’s many pubs. So ended a chapter in the lives of several men brought together by circumstance.

And circumstance had a part to play in Aldridge’s life in the following days because a young lady named Harriet Phillips arrived in Maryborough from England. She was to become his wife and they were to have five children.

The author, Warren Nunn, is Henry Aldridge’s great-great grandson, through Aldridge’s daughter, Emily Ellen Sophia (1876-1970).

How Henry Aldridge recalled the trial

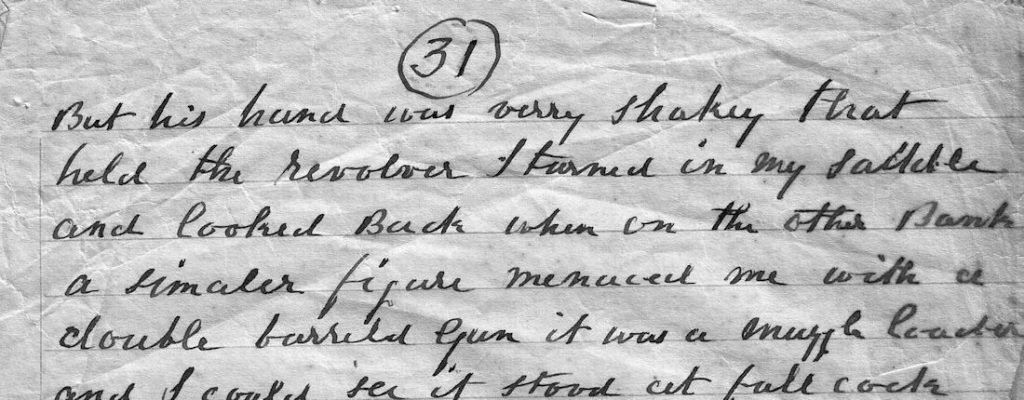

An excerpt from Henry Aldridge’s memoirs in which he describes how he was held up by bushrangers near Gympie.

(Following is an extract from the Henry Aldridge’s memoirs that gives details of the hold-up in 1868)

But I got started and went to Imbil Station when I called there and bought a piece of steak to roast on the coals when I intended to have a rest and spell my mare for an hour or two. But man proposes and God disposes and I did not get the rest for about three miles from Imbil, while going through a patch of brigalow in a boggy creek, I heard a voice call out: “Stand you bugger or I will shoot you.”

Looking up I saw a figure with a long shirt out of a blue blanket covering me with a pistol but his hand was very shaky that held the revolver. I turned in my saddle and looked back, when on the other bank a similar figure menaced me with a double-barrel shotgun. It was a muzzle loader and I could see it stood a full cock with caps on the nipples and he was as steady as a rock.

They made me get off in the creek and marched me in front of them off the road. I should say half a mile or better. They had taken my mare away from me and all the money they got from me was the change I got when I bought the beef at Imbil and the receipt I got from the bank there (which) which I found after where I was tied up.

They tied my hands behind my back and made me sit down on the ground by a … sapling, and because I did not sit up close to the sapling, they hit me on the head with either a stick or the revolver. I was stunned for a time. When I came to myself, I was fast to the sapling and I wanted a drink of water. I then heard footsteps and looking up and saw the man with the gun and his face was uncovered and I saw him very plain.

As soon as he saw I was conscious he covered his face with a coloured handkerchief and said: “Oh, you are not dead.” Then I asked him for a drink of water. He said he had no time to get me one, but his mate would be along directly.

His mate did come along but he would not give me a drink but he gave me a chew of my own tobacco and said: “If I did not make a noise he would let me go at sundown.

This was in the month of June about 10am, but they never come and let me go, but I got away from the sapling just about daylight the next morning with my hands still tied behind my back and legs tied around my ankles.

After a great many attempts to stand – with several falls – I at last succeeded but I was grazed and bruised all over. I started to jump for the road, but I made very slow progress as the country was very rough. I sat down once and tried to cut the string through that bound my ankles but could not suffer the pain. Well, at last I got in sight of the road, when welcome sight I saw four men with swags going towards Gympie.

When I coo-ed to them they seemed to hesitate about coming on to me, as I was naked and covered in blood and dirt from head to foot. When they cut the string that bound my wrists and ankles, when I must have swooned away (for) when I came to they was giving me a drink of water and they found me some clothes after washing me in the creek to which they had carried me.

These same four men had been stuck up and robbed the night before. That was the same day as I was. Only I was tied in the morning and them in the evening, they was tied two and two but one of them having lost a finger, his hand was smaller than his wrist. He was able to slip his hand and unloosened the rest. Well, I went back to Imbil with these men and I got there they put me to bed after giving me some beef-tea.

As I lay in the bunk I was visited by a trooper and a gold buyer, and as they told me they asked me questions about the rangers, but which I answered, but I had no recollections of doing so. In about a week I was able to ride to Gympie as my mare was found by one of the station hands about a mile from where I was stopped by the bushrangers.

My saddle also was found on top of the Yabba range close to the road with one of the blanket shirts the rangers wore. I was asked by the police to go to the courthouse and report, which I did, when the inspector – I think his name was Lloyd – asked me all particulars about the stick up. He then showed an album of lots of photos of men, and after looking at them I came across the photo of the man that I saw his face uncovered, after I came to myself after I was tied up. I then said that was one of the men – the one that held the gun.

The inspector said: “I know him, we shall have no difficulty in getting him captured as he was then keeping a shanty on the road on the Brisbane side of the Yabba (Jimma) range. He also asked me if I saw him and knew him when he was in the hands of the police.

About a week after this, I was up in the Jimma township as I had not started work at the claims, as I still paid a man to work for me, when a constable came after me and told me to come and identify the man, but I was not to forget what the inspector told me. The place where they had the police station was about half way between Jimma creek rush and the Sunday gully rush. It, the station, was only bark and slabs, but they had (a) window facing the way he was coming and the constable said: “Look, Sergeant McCarthy has him framed in the window,” so I looked up and it was the same face I saw uncovered in the scrub and also in the police album.

I then went into the hut and then I heard his name for the first time as “Troden” alias “Podgey”. When I was asked by the sergeant whether I knew the man, I said: “No, I don’t know him, I don’t think I ever saw him before”. Podgey then turned to the sergeant and said: “You can let me go now sergeant”, but McCarthy said: “No, Troden, I shall have to take you down to Gympie as the warrant says, and this man – pointing to me – “has to come too, you will be all right.”

There is one instance I ought to mention, that is when he arrested Podgey, he told the constable that was with him to keep Podgey covered with his revolver. While doing so, the revolver went off and the bullet passed between McCarthy and Podgey, shaving close to Podgey, when Podgey said quite cool: “That was a close shave, sergeant.”

Well, after I had squared up matters at the claim – we was still getting good returns, I went down to Gympie, and at the police court hearing, when I was giving evidence, when I said “he was the man”, the PM looked at me, but the inspector told the magistrate that he had told me to not recognise him at Yabba as they might have trouble in bringing him down to Gympie.

They had another name Blake in the dock with Podgey, but I could not identify him. So Podgey was committed for trial at Maryborough, and I was bound over to appear at his trial. He was also charged the same day with sticking up the other four men that cut the strings that bound me.

They all identified both Podgey and Blake, so they was both committed for trial on that charge as well. I cannot remember what month the trial took place or whether it was in 1868 or 1869, but I think it must be the later year. (It was in the month of July 1868 the assault took place, and the court case was heard in Maryborough Criminal Sittings on Saturday September 26, 1868. Case concluding Monday 28th).

I then went back to Yabba and sold out my interest. In fact we all sold out as we though it was worked out. We sold it to some storekeeper at Jimma. They put on wages men to work it.

Paid them for a week or two. When they gave it up to the men they had working for them, who made a good thing out of it, getting nearly as much gold out of it as we did, by breaking the bottom of an old dried bed of a gully which was running the same way as the creek we worked. It must have been the old original creek years before and we never thought it was worthwhile to try. Well, I now wished them all goodbye at Jimma (and) went down to Gympie, disposed of all my shares in the reefs I was backing in, and went down to Maryborough to wait for the trial.

I stayed at the “Steampacket Hotel” Kent Street. Well, the trial took place but I was not called to give evidence, but still had to attend the court and the case of the other four men was called when they all swore to the two both Podgey and Blake. The jury retired and in about 10 minutes returned with a verdict of guilty.

How Henry Aldridge described the judge’s comments.

When the (judge) looked over at the prisoners and told them that it was lucky for them that they was not on trial for the other case that was mine, so he started to pass sentence on them. I shall never forget his words. The words were: “Prisoners at the bar, you are justly found guilty of highway robbery and the sentence I shall now pass on you will be 20 years penal servitude and as you bound them in bonds of rope, I will bind you the first three years in irons.” I went and saw the irons riveted on them at the lock-up and they was then marched down to the steamboat to take them to the Brisbane jail.