Henry Aldridge was born in a pub. From his first connection at the Black Horse Inn at Welwyn, Hertfordshire, England in the 1880s to his last with the Royal Hotel at Bouldercombe, Queensland, Australia, in the 1910s, it was challenging at times.

When I took the above image in 2020, the Royal Hotel, was not operating.

Former Black Horse Inn at Welwyn, Hertfordshire, England that was operating as The Stable Door Restaurant when this image was taken in 2004. Henry Aldridge was beershop keeper there in 1883.

Just over 100 years earlier, Henry Aldridge was struggling to keep the hotel afloat and ended up in court trying to recoup money from a messy deal to sell the pub.

While he was forced to sell his tenancy in the Black Horse Inn back in 1885 due to a collapse of another business that left him deeply in debt, his experience back in Australia about 30 years later was far more complex.

Henry Aldridge did well in many of his business ventures but as is typical for many people, there were some failures.

When Henry sold the Royal Hotel to Florence Hickey in 1917, the deal did not turn out that well for both parties.

It ended up with a court case that left Henry Aldridge out of pocket.

From January 1908, Henry paid £1 a week to rent the Royal Hotel at Bouldercombe from the owner Mrs Sarah Heiser.

She died in 1909 and, in 1911, Henry bought the pub for £300.

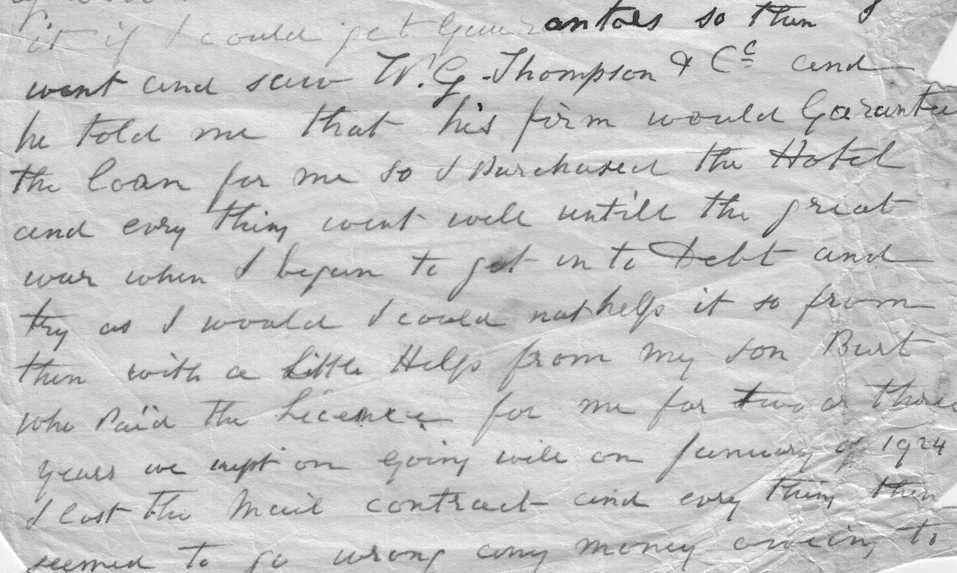

This is how Henry described the situation:

Well I was still in the hotel and paying rent when the landlady Mrs Heiser died and her son Abe Heiser became the owner of the hotel and he wanted more rent or he would pull it down or build cottages at Mount Morgan or he would sell it to me for 300 pound. Well I said I would take it if I could rise the cash to buy it so I went to Rockhampton and saw the manager of the Royal Bank and asked for the loan of 300 pounds. He told me he would let me have it if I could get guarantors so then I went and saw W. G. Thompson & Co and he told me that his firm would guarantee the loan for me.

From 1914, when World War 1 started, the pub began to lose money and Henry went into debt. His son Burt even had to pay his license.

In November 1915 Henry made a deal with Mrs Florence Hickey in which she bought the pub, as well as his mail-run business. That was to be a poor decision.

As part of the agreed amount of £450, Henry received £150 cash and the balance was pledged in promissory notes.

But Mrs Hickey faced the same financial problems as Henry and abandoned the pub. Her promissory notes weren’t honoured which led Henry to take the matter before a Small Debts Court in 1917.

Because Henry was still the lessee, he resumed his tenancy in the hotel. Mrs Hickey had transferred the license back to Henry.

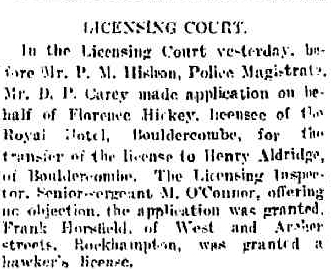

April 1917: Florence Hickey transfers hotel license to Henry Aldridge.

But the issue of outstanding debts had not been resolved and the parties ended up in court.

Mr. E. R. Larcombe represented Henry, while Mr. K. Allen appeared for Mrs Hickey and her husband George.

Mr Allen asked Police Magistrate, Mr Hishon if the Court had jurisdiction in the matter.

He said that would depend on the amount involved and he would rule on that later.

In answering Mr Allen, Henry said the value of the stock at the time of the transfer to Mrs Hickey was about £13. He also owed W. G. Thompson and Co., Rockhampton, for goods supplied.

Apart from the mortgage, Henry said he could not remember if there was another document between the parties at the time of the sale and transfer to Mrs Hickey.

“I’m 73 years of age, and my memory is not that good,” Henry said.

Henry said he didn’t know that Mrs Hickey had mortgaged the hotel to William George Thompson and Donald Walter Jackson, trading as W. G. Thompson and Co.

There’s an obvious complication to note here because both Henry and Florence Hickey had dealings with W. G. Thompson and Co.

It was at this point in his evidence that Henry’s case began to unravel. In describing the agreement, Henry said he did not sell the mail contract but that the agreed price of £450 was for the hotel license and goodwill of the house. The mail contract was attached to the house.

It’s unclear what Henry meant about the house and the mail run, but further questioning showed that Henry had no right to sell the mail run. Only the Postmaster-General had jurisdiction over that matter.

Henry Aldridge about the time he was fighting to keep the Royal Hotel operating.

Mr Allen asked: “Do you expect the payment of the undue promissory note and likewise to retain the hotel?”

Henry replied: “Yes; unless they give back the mail contract. If they give it back I shall not want payment for the promissory notes. It is worth £50, probably more.

Mr Allen: “Does the value of the mail contract make up for the worth of promissory notes?”

Henry: “Yes. Mrs. Hickey says it is worth about £70 a year, and it has several years to run.”

After further evidence and cross-examination regarding the promissory notes, Mr Allen made the point that because Henry Aldridge had endorsed the notes to another party (W. G. Thompson and Co.) he didn’t have any rights that the Court could address.

Mr Allen asked for a nonsuit on the grounds that Henry was “not the holder of the bill, he having endorsed it over to another, and no longer had any rights under it”.

He also said part of the consideration given for the promissory notes was illegal as the mail contract could not be handed over without the consent of the Postmaster-General.

That made the whole contract void, because the “illegal could not be separated from the legal consideration given”.

Mr Hishon then read out a section of the Act and said he had no alternative than to strike out the case.

The Police Magistrate allowed £2 12.s 6d. professional costs; £2 18s for the defendant’s attendance; 7s. 6d. witness’s expenses; and 1s cost of Court.

As Henry later revealed in his memoirs, he struggled on at the pub for a couple of years and then quit.

An expanded account of Henry Aldridge’s life is told in my book I’ll Show You Gold which is available both in print form and in a Kindle edition.

Excerpt from Henry Aldridge’s memoirs that mentions Bouldercombe Hotel.